Thank you for this question from the side there. I’d answer with another question – “Have You Tried Drawing?”. It’s really something else to give it a try.

“But I can’t draw.” You say. That’s not true! Turns out that’s a lie your left brain tells your right brain.

I was in the “I can’t draw” camp until a few years ago. I’m still not very good, but I don’t irrationally handicap my abilities anymore. Here’s what happened:

I’ve had this drawing book on my shelf for many years. I don’t know how long, maybe since college. I never read it. Never even flipped through the pages. It sat on the shelf as one of many subtle guilty aspirational reminders – next to the Write An Animated Feature, or Design A Website, or Improve Your Vocabulary. But we were heading into a long holiday weekend and I wanted to bring a book or something as an excuse to get off the doom-scrolling social media train.

The book is called “Drawing On The Right Side Of The Brain” by Betty Edwards and it will be effective at changing how you see the world. Learning to draw is learning to see things differently and once you do, the world is more dynamic and interesting in every way. I’m never bored anymore.

Her theory is that folks stall out between 10-13 years old, when they start to want to draw realistic things – cars, monsters, pets, people. But language learning has been emphasized so much over visual learning at this point, that the left side of the brain shits on the right side’s effort pointing out every flaw like a bully in your own mind. “You suck at drawing. That dog looks terrible.”

So most kids give up.

“I’m not a person that can draw. I don’t have the genes.”

The ones that figure out how to turn off the critic long enough end up as successful artists if they keep at it. But Betty makes a compelling case that the rest of us shouldn’t have given up. We’re all capable. In fact it’s innate within us. (Keep funding those public school art classes, people! It’s worth it.)

DRAWING WITH FEELINGS

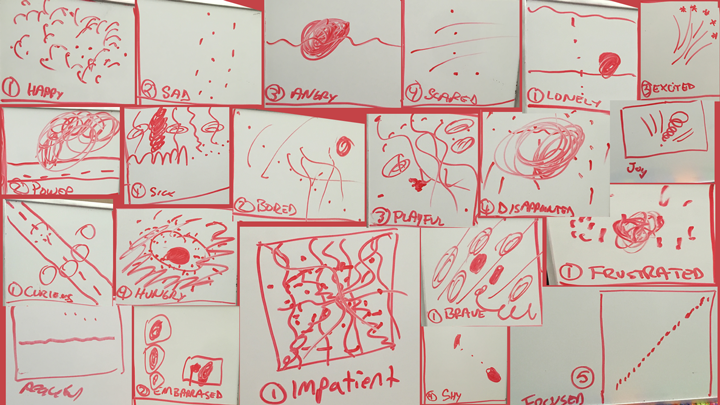

Two stories that tripped me out. The first was an exercise Betty would have her classes do that went like this. You can try it too:

Take a sheet of paper and draw a break line down the middles so there’s four quadrants. Then write an emotion at the top of each quadrant. “Happy“, “Sad“, “Angry“, “Fearful.”

Now, without using words or typical symbols (no faces, no emojis), draw those emotions. Lines, curves, squiggles, dots are fair game.

What happens when you compare the result is that you discover this amazing thing – that we all have a shared unspoken universal visual language. Sad tends to be small scrawls falling to the bottom of the page. Angry has lots of hard stomps. Fearful is this ball of energy. Happy has a lightness to it, often with upward motion or higher elements.

Here’s a few tries with the family:

Isn’t that neat? That we’re absorbing meaning on a different subconscious visual level in addition to the overbearing language level. Most people still perceive what was expressed, even when removing the title emotions. And it turns out that this framework is remarkably consistent across cultures.

This is another rabbit hole, with applications to theater and film-making and all sorts of other creative endeavors. That’s yours to explore now.

THE UPSIDE DOWN

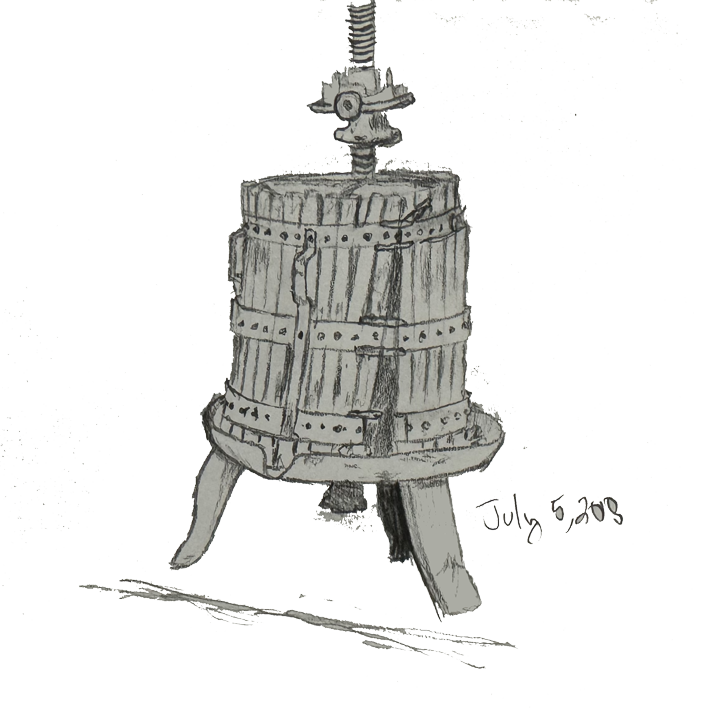

The second trippy exercise was the upside down drawing challenge. If you take a sketch or picture and flip it upside down, then try to draw what you see, that’s enough to get people to draw better.

Wait, why? It’s the same picture, isn’t it? Well, the theory goes that the left side of the brain is constantly short-handing the world. A face can be represented as a simple stick figure. It doesn’t need to be fancy, the left brain says. Just half-ass it and get a move on. There’s too much complexity in the world, too much information to absorb so the brain throws up it’s proverbial hands and says F^$k it, go with the bare minimum.

But flipping the drawing upside down breaks the shorthand that the left side of the brain is trying to do because nothing looks correct. Now the brain pays attention to the details, and the hand does a much better job representing the real thing.

And Betty used that as proof positive that our “I can’t draw” mentality is bullsh!t.

You can.

You did.

Don’t listen to your stupid language brain.

This book spends a lot of time with techniques for how to turn off that nasty critic. Most of them involve making ol’ left brain so bored that it gives up.

And when the left brain gives up, students often find themselves in the fabled “FLOW STATE” – that zone where you lose track of time, you don’t notice being hungry or uncomfortable, your perception of the world around you disappears and it’s just you and the work.

It’s trance. It’s meditation. It’s a lovely and strange feeling.

And after a few days, you start to find the complexity fascinating. You’ll notice that rarely in the world are there straight lines and perfect corners.

Everything is organic and curved and intertwined.

But I don’t want more complexity in my life, you say! Not to worry. It’s not added stress. It’s the opposite! This complexity is calming in a paradoxical way – What was once just a mass of leaves is now a kaleidoscope of fascinating shapes and individual beauty. The part of one’s hair around a forehead, the way a dog’s ear flops, the point where a telephone pole meets the sky – all hypnotic now in their infinite shapes and overlaps and intersections.

These glimpses you now have into a higher design start to act like that feeling you get when you look for a long time across a vast ocean, or stare into a telescope at a distant star. Humbling and grounding, and readily accessible without the need for a sailboat or a dark dark night sky.

The mind becomes less busy when thinking of larger things then oneself.

Then Betty gets into fundamentals of drawing in a way that clicked for me than the Drawing The Marvel Way and The Animators Survival Kit did.

Draw what you see.

It was so simple.

Draw what you actually see, not some rudimentary construct or meme representation of a thing that your mind substitutes. Draw the rest of the f’in owl.

The faces and the hands, those are the hard things to draw not because they’re complex but because those are the most familiar and most short-cutted in your mind. I know that’s not a word. The busy mind says why draw complexity when a stick figure with a little u for a smile will do?

GET INTO A NEGATIVE SPACE

The one concept that I found most helpful is the idea of looking at the negative space. Complicated shapes become simpler when you look at the surrounding shapes – the parts that aren’t there. It’s why great animators focus on the silhouette for memorable character design. It’s also clever in logo design, with the now famous arrow hidden within the FedEx logo:

Now you can’t unsee that arrow from now on. There, I wrecked it for you.

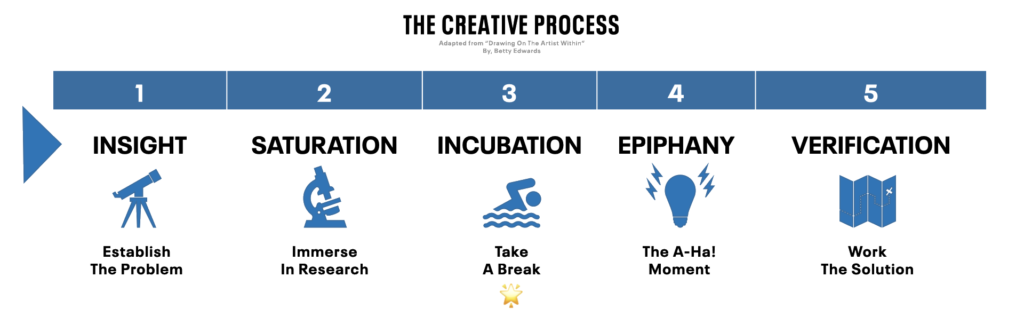

Betty has a follow-up book called “Drawing On The Artist Within” that focuses more pointedly on the creative process, and has one of the more succinct theories of how creativity works. I’ve adapted it here as a visual in 5 phases:

That 3rd step is the one that’s most often skipped because it doesn’t feel like work. Walking, driving, gardening – that’s not work. But it is for your wild brain!

Bury it full of information, and set it on a problem, and the ol’ Brain with a capital ‘B’ will subconsciously plug away at the solution. There’s so many stories about inventors and scientists having that epiphany moment in the least of work-related places. Newton under a tree.

Alrighty, that’s enough. Go take a walk, sit under a tree, stare at the leaves. Observe the world differently and never be bored again. And thank Betty Edwards for helping us really see what’s actually right there in front of us.

🎨

Leave a Reply